Musée d’Orsay is currently showing the exhibition L’art est dans la rue. The spectacular development of the poster in the second half of the 19th century was a phenomenon that was widely commented on by contemporaries. Printed propaganda had flourished during the French Revolution. But from the mid-19th century onwards, cities – particularly Paris, where posters took on particular importance – were the setting for the circulation of a new type of poster, illustrated and in colour. It is this break with the past that the exhibition sets out to explore. Embraced by the artistic avant garde, the poster embodied “modern life”, as it was then known, and acted as a powerful indicator of the changes taking place in a rapidly evolving society. This exhibition explores the roots of a phenomenon that was not just artistic and technical, but also urban, economic, social and political. Through a unique collection of works assembled here for the first time, the exhibition also shows how these many images helped to shape the myths and representations of the so-called Belle Époque.

Image above: Théophile Alexandre Steinlen (1859 – 1923) Imprimerie Charles Verneau (Paris) Affiches Charles Verneau. « La Rue », 1896 Lithographie en couleurs, 240 × 300 cm Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, département des Estampes et de la photographie Photo BnF.

Poster Transforms the City

Coinciding with the rise of consumerism, the colour illustrated poster underwent intense development in the second half of the 19th century, so much so that its proliferation in cities was viewed as a social phenomenon. Although ephemeral, this new medium played a part in the metamorphosis of urban spaces: as the art critic Roger Marx wrote, “like society, the street has been transformed”, and the poster became an essential part of that transformation. The omnipresence of posters provoked contrasting reactions: they were seen as either a blessing of modern life or, on the contrary, as a form of visual pollution. Freedom of commerce and freedom of expression – which encouraged these inflated images – would soon come into conflict with an emerging heritage movement that promoted the protection of historic monuments and the urban landscape.

The Real Architecture Is the Poster

While associations battled against the proliferation of posters, a radically different vision was also emerging. Posters now had their supporters in the art world, who believed they transformed the streets. Their praise often went hand in hand with virulent criticism of Haussmannian city, as Joris-Karl Huysmans put it when he wrote of the incongruity of Jules Chéret’s posters, which “throw off balance, with their sudden intrusion of joy, the stationary monotony of a penitentiary setting”. It was in this spirit that journalist and essayist Maurice Talmeyr wrote at the end of the 19th century: “The real architecture today, the one that springs from ambient and pulsating life, is the poster, the abundance of colours under which the stone monument vanishes.”

Billposters: Between Stereotype and Reality

A key player in the spread of posters throughout the city, the billposter (or billsticker) was an iconic figure in Belle Époque Paris. His easily recognisable tools of the trade were adopted by celebrities who dressed up as billposters, such as Prince Napoleon at a ball at the Opéra in 1883. Portrayed by writers and early filmmakers, billstickers were an essential element of picturesque depictions of the streets and small trades of Paris. Often stereotyped, these images – distributed particularly in the form of postcards – overlooked the difficulties of a risky profession, where falls were sometimes fatal.

The Invention of the Colour Illustrated Poster

Official posters have existed in France since 1539, when Francis I first decided to post his royal decrees. Over time, they grew to face increasing competition from a variety of placards, texts and pamphlets, particularly following the French Revolution. Illustrated posters began to appear from the 1830s onwards, notably for bookshops, designed to entice readers to read new publications. Modest in size and printed in black, they were confined to interior use. The industrialisation of the printing process led to the advent of large-format colour lithography at the end of the 1860s, with large, colourful posters taking over city walls. Novelty shops, theatres and even newspapers gradually adopted this new advertising medium.

The Pioneers of the Colour Poster

Jean-Alexis Rouchon was the first to produce large-format colour posters in the 1840s. Using wood engraving in particular, his workshop mass-produced these striking posters by hand, with their unusual formats and vivid colours. A new stage was set with the arrival of Jules Chéret, recognised as the father of the modern poster. After training as a lithographer and draughtsman and spending several years in London, he opened his Parisian lithography workshop in 1866. His technical mastery and artistic talent ensured the success of his posters, which grew increasingly vibrant in colour. In the 1880s, he became the leading name on the French poster scene, and his work drew attention from artists and art critics alike. By the end of the century, lithographic printing had become a genuine art industry.

The Lithographic Technique

Lithography is a technique for printing a flat design from a stone, either prepared limestone or artificial stone. Developed by the German printer Alois Senefelder in the late 1790s, lithography is based on the chemical principle of the antagonism of grease and water: the drawing made on the stone with a grease pencil attracts the printing ink. At the same time, the unmarked surface of the stone, saturated with water, repels the oily ink. The image to be reproduced is broken down by colour: each colour generally corresponds to one stone. The sheet of paper is successively pressed onto each of these stones to reconstitute the image. Like all printmaking techniques, the lithographic process inverts the image: a symmetrical image to that on the stone is printed on the paper.

Posters and Censorship

Censorship refers to the intervention of political or religious authorities to prohibit the publication of a text or image, or the performance of a show, on the grounds that these works undermine their values. It is a preventive system whereby the State grants approval to publications before they are published. In France, censorship endured until the 1881 Freedom of the Press Act, with the exception of theatrical censorship, which continued until 1906. Nevertheless, after these dates, the authorities, through judicial institutions and the police, still controlled publications after the event and prosecutions could be brought. Many late 19th-century artists openly criticised the morality of these actions, sometimes falling victim to them.

Posters Stimulate Consumption

Advertising, mail order and department stores were just some of the commercial innovations that stimulated consumer spending in the second half of the 19th century. The success of these “cathedrals of modern commerce”, as Émile Zola called them in Au Bonheur des dames (1883), was based on one core principle: selling in high volume and quickly. Having become a mass medium, the colour illustrated poster quickly established itself as a weapon in the arsenal of these new commercial strategies. Seduced by its aesthetic qualities, advertisers turned to some of the most renowned poster artists, such as Jules Chéret, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Alphonse Mucha. The medium became a fertile field for experimentation, with an increasing emphasis on commercial effectiveness. At the start of the 20th century, this evolution was epitomised by Leonetto Cappiello, whose pure, powerful graphics were entirely devoted to the advertising message.

The “Cathedrals of Commerce”

Around the middle of the 19th century, the number of novelty shops in the capital increased from 300 in 1830 to over 1,300 in 1862. These stores were the first to encourage the growth of consumerism, essentially a middle-class phenomenon. It was during the Second Empire that department stores really came into their own, characterised by a major shift in scale in terms of sales volumes, but also in terms of the number of customers and employees. Advertising played a crucial role in the development of these establishments, whose success was based on speed of stock rotation. Their architecture was monumental and theatrical, both inside and out, offering customers an exhilarating experience.

Advertising for Everything and Everyone

The illustrated poster quickly established itself as an indispensable medium for modern advertising. Despite the cost and the ethical issues it raised, many brands embraced its potential and reaped the benefits. Against a backdrop of growing consumerism fuelled by the industrial revolution, posters were used to promote every variety of product. Making extensive use of stereotypes, they were skilfully adapted to the nature of the products and the consumers they targeted. The advertising targeting process was gradually put in place: advertisements were aimed at a male clientèle, but also at women, because of their influence on everyday purchases, and at children, for whom specific promotional items were designed.

“Modern Life”

The law of 29 July 1881 on freedom of the press encouraged an explosion in commercial advertising, particularly in Paris, where the city’s inhabitants enjoyed greater purchasing power than the rest of the French population. As a recent invention that was constantly being improved, the colour lithographic poster was the ideal promotional tool for advertisers. The capital became a showcase for “modern life”, transformed by new modes of consumption and new commercial practices. At the end of the 19th century, posters played a decisive role in the success of the bicycle and the development of tourism. Embodying the modernity of a society turned upside down by the industrial boom, posters also helped to shape the way it was represented.

The Avant Garde and the Poster

In the 1880s, the poster became an artistic medium in its own right, hailed by art critics who praised the “poster masters”, of whom Jules Chéret was recognised as the pioneer. Alongside artists who specialised in posters and illustrations, a number of painters also entered the field in the 1890s. Artists in the Nabi circle found the poster a fertile ground for experimentation and expanding their art. Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, Maurice Denis, Henri-Gabriel Ibels and, of course, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec all contributed in varying degrees to this new art form. In this medium, they rediscovered the specific features of their own pictorial work: absence of traditional perspective, the use of flat areas of bright colour, and synthetism of compositions.

Poster Mania

Posters became the object of a genuine craze during the 1890s. They attracted collectors to such an extent that the term affichomanie (“poster mania”) was coined. For enthusiasts, a specialised market in illustrated posters emerged, similar to that for prints, with its own exhibitions, dealers and publications. Some poster prints included rare proofs, specially designed for affichomaniaques and not to be displayed in the street. Variations on famous posters, such as those by Alphonse Mucha for Sarah Bernhardt or some by Toulouse-Lautrec, became highly sought after. Some were kept in large portfolios, while others were displayed in special furniture for collectors.

Exhibition Posters

The official Salon, whose pre-eminence began to be challenged from the 1860s onwards, saw increasing competition from exhibitions held by independent organisations, some of which specialised in specific fields – decorative arts, watercolours, printmaking, etc. – while others aimed to establish a dialogue between the arts. These events often had their own promotional posters, probably intended less to attract the public than to mark the event, as shown by the multidisciplinary exhibitions organised from 1894 onwards by the Salon des Cent at the headquarters of the magazine La Plume. Forty-three posters were created, each by a different artist. The diversity of personalities and styles gives an idea of the extent of the interest in posters in artistic circles.

Shows for Everyone

Show business producers relied heavily on illustrated posters to attract audiences in what was then a very dynamic and competitive sector in Paris. Distributed mainly in the vicinity of the Grands Boulevards, a multitude of posters were displayed on easels in front of theatre entrances, stuck on walls or on Morris columns. Frequently replaced as programmes were updated, they contributed to the development of mass culture. The painters who frequented these venues sometimes developed connections with certain performers, to the point of taking control of their image: this was the case for Toulouse-Lautrec with stars of cabarets and café-concerts, or Alphonse Mucha with Sarah Bernhardt. More generally, the world of the stage, from theatre to circus, from opera to cabaret, fascinated painters and became a pictorial subject in itself. The familiarity of these two worlds – show business and painting – was thus expressed in both the posters and in pictorial practice.

Mucha and Sarah Bernhardt: The Invention of an Icon

Sarah Bernhardt was certainly the first actress to control her own image. As her fame grew, she was able to demand that she appear at her best on posters. At the height of her fame in the mid-1890s, a close collaboration with Alphonse Mucha resulted in the creation of eight iconic posters. Tasked with creating the poster for Gismonda in a hurry, Mucha captured the uniqueness of the actress he had already drawn on stage. He offered an idealised vision of her, also highlighting the accessories for each of the roles that sum up the play: the martyr’s palm, the camellia flower, the bloody dagger, and so on. In this way, he combined the advertising needs of the poster with the wishes of his subject, who wrote in her autobiography: “I ardently resolved to be somebody, all the same!”

The Bohemian Personalities

A fan of cabarets and café-concerts, in the 1890s Toulouse-Lautrec created posters for a number of celebrities: Aristide Bruant, poet, singer-songwriter and cabaret-goer, as well as singers and dancers such as Yvette Guilbert, May Milton and La Goulue. Other artists including Théophile Alexandre Steinlen, and later Leonetto Cappiello, also took up the theme. Each personality was characterised by physical features or accessories that defined his or her character: hat, gloves, a slender or bulky silhouette, recurring stage act, etc. These representations oscillated between bohemian picturesqueness and individualisation. These early “stars” were making a name for themselves as well as an image, assisted by poster artists who knew them, attended their performances and frequented this milieu.

The Spectacle of Otherness

Alongside the earliest stars, whose names could be found on the posters, show business was largely based around the staging of the “world” as seen from Paris. Audiences were invited to discover the supposed representatives of faraway societies colonised by Western empires. Posters thus emphasised the picturesque features – costumes, accessories – in specialised acts declared to be “unprecedented”. The bodies of individuals were also part of the show, decorated and dressed in ways never seen before by audiences, and depicted as endowed with abilities such as strength, flexibility and balance. These posters laid the foundations for representations based on the essentialisation of individuals, their reduction to fantasised characteristics, paving the way for the overtly racist discoursesof the 20th century. Posters would go on to play a much darker role in the spread of racism.

Politics in the street

The golden age of the artistic poster came at a time when social concerns were at the forefront of the Third Republic’s aspirations for profound change. The architect Frantz Jourdain considered that “people learn as much in the street as they do in the classroom”, and in 1892 he raised the question of the artist’s social responsibility in an article with a powerful title: “L’art dans la rue” (“Art in the Street”). Accessible to all, the poster was placed at the heart of the debate on social art by a number of writers, including Roger Marx, Joris-Karl Huysmans and Gustave Kahn. As the forum where posters were displayed, the street also became a space for expression in its own right. Less violent than before, political life saw the emergence of new practices, such as street demonstrations. It was against this backdrop, marked by a rise in extremes in the capital, that the first illustrated political posters appeared.

The Poster as the Focus of Social Art

Disseminated in public spaces, the poster became the preferred medium for “people’s art”. For Roger Marx, it was “the mobile, ephemeral canvas demanded by an age eager for popularisation and change”. In 1893, in the pamphleteering journal Le Père Peinard, Félix Fénéon praised the poster and launched a diatribe against the Salon: the poster was, he wrote in caustic slang, “painting that’s more elegant than the liquorice juice daubs that delight the upper-class arseholes”. With this scathing plea, the new art form established itself as a genuine counterculture, in contrast to academic art, which was considered bourgeois. The illustrated poster, developed with the rise of consumerism, found itself at the heart of the socio-political divisions of fin-de-siècle Paris.

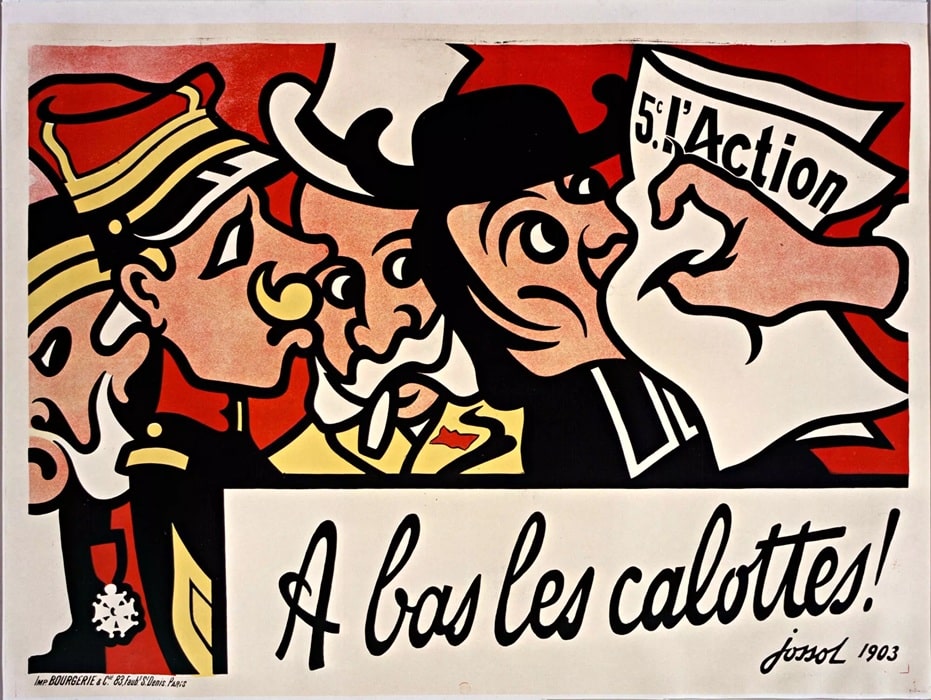

From Social Novels to the Militant Press

Enshrined in the law of 29 July 1881, the newly asserted freedom of expression and the liberalisation of billposting encouraged the emergence of the first illustrated political posters in public spaces that had long remained under tight control of the State. Initially, these posters spread mainly through advertising for social novels, published as serials in large-circulation newspapers. Faced with competition from newspaper capitalism, the militant press struggled to survive. The spectrum remained broad, however, ranging from radical right-wing, antisemitic and nationalist titles to far-left publications with a volatile, mainly Parisian readership. This was particularly true of the anarchist papers, which featured contributions from leading artists. Posters with overtly political content appeared on the streets to promote these militant publications.

Towards the Propaganda Poster

The turn of the century saw the diversification of illustrated posters with political messages, which until then had been essentially linked to advertising campaigns for books or newspapers. Trade unions, political groups and revolutionary committees all took up this new means of mass communication. Political artists such as Théophile Alexandre Steinlen and Jules Grandjouan created a graphic rhetoric designed to strike a chord with public opinion in the urban space. Breaking with the intimate visions of press cartoons, these monumental, vertical compositions were designed to make passers-by gaze upwards. This mural language had a lasting impact on poster propaganda, which developed during and after the Great War.

WHEN?

Exhibition dates: Tuesday, March 18 to Sunday, July 6, 2025

Opening hours: Tuesday to Sunday: 9:30 am – 6:00 pm, Thursday: 9:30 am – 9:45 pm

WHERE?

Musée d’Orsay

Esplanade Valéry Giscard d’Estaing

75007 Paris, France

COST?

Regular: 16 EUR

Adult with a child: 13 EUR

Late opening on Thursdays: 12 EUR