1: Documentation of the intervention res-o-nant LIVE in Berlin-Kreuzberg during Berlin Art Week,

September 2018, photo by Ladislav Zajac, archive Mischa Kuball, VG Bild-Kunst Bonn 2019

“The official name of the project is ‘Jewish Museum’ but I have named it ‘Between the Lines’ because for me it is about two lines of thinking, organization and relationship One is a straight line, but broken into many fragments, the other is a tortuous line, but continuing indefinitely.”

– Daniel Libeskind

„Libeskind is not merely translating his architectural designs into a building … (…) going through the winding hallways of his museums, their ghostly quality resonates with [Paul] Celan’s poetic structures of the uncanny.”

– Eric Kligerman, Sites of the Uncanny. Paul Celan, Specularity and the Visual Arts, Berlin 2012

„It [ the Jüdische Museum Berlin] feels almost like a fortress, so sound is an appropriate medium to circumnavigate these restrictions within the space.”

– Mischa Kuball, 2018

Almost 20 years have passed since the completion of the prominent new building complex by New York architect Daniel Libeskind on a Kreuzberg site where Berlin’s first Jewish Museum was located until 1938. Berlin’s museum and memorial landscape has developed just as rapidly in this time as gentrification is likely to change centrally located districts of Berlin. While the world-famous museum may appear to be an unmistakable architectural landmark of the city in the midst of these upheavals, it is nevertheless a strictly guarded building, entered through a security gate in the baroque entrance building, whose hermetic shielding from the urban environment marks it as a cultural institution worthy of special protection. The institutional success story of the Jewish Museum, a federal institution, is also remarkable in a European context. Barely a decade passed between the planning of a new building for the Berlin Museum and the then affiliated “Jewish Department” and the opening of a museum dedicated to Jewish-German culture and history in the so-called “post-reunification period”. This, however, brought profound changes in everyday life, images of history and relations to a post-Wall world not only for Berliners but for all Germans. This simultaneity of events has given the building project, which was also linked to the claim of an urban and mental departure into a common metropolitan future in the centre of Europe, a special position among the redesigns of Berlin museum buildings that have been realised in the meantime. The building is a notation or a text, at the same time a memorial to history, an artistic work and, in comparison with other Jewish museums in Europe, can itself be assessed as an unrepeatable conceptual experiment due to the interweaving of historical, political, cultural conditions, functional assignments and metaphorical references to postmodern Holocaust reflection in the arts.[1] The building is a monument to history and an artistic work.

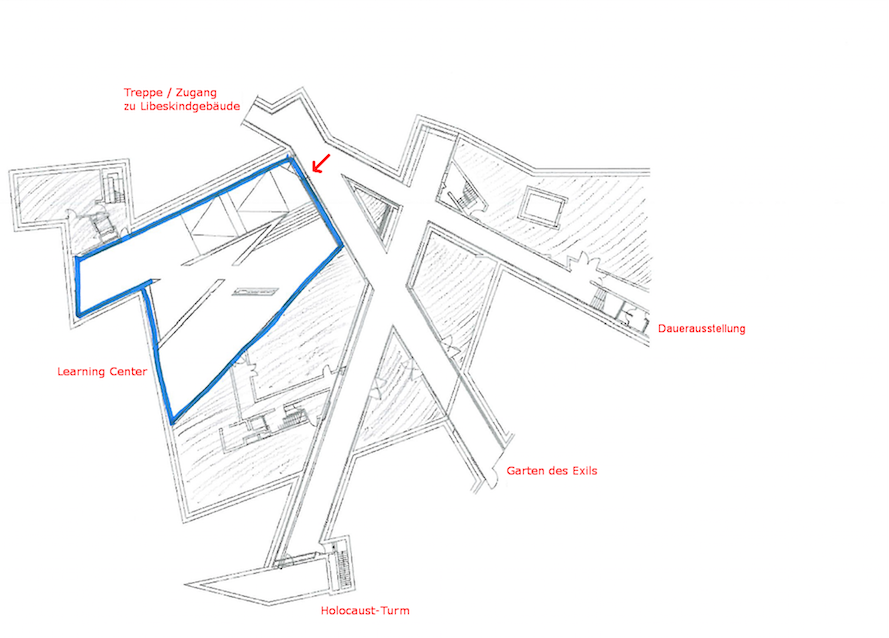

Over 10 million visitors from all over the world came in the first 15 years to experience the spectacular architecture, the exhibitions that opened from 2002 and changing special programmes. The architect’s design period began in the late 1980s, still in the Reagan era, under the influence of postmodern deconstruction of 20th-century architectural theories, in the field of tension between the international museum boom and post-memorial reflections on the Shoa from the perspective of everyday experiences of war and crisis in literature, film and contemporary art.[2] The building project was almost shelved as unfeasible and dysfunctional after German unification, had the Bundestag not overruled the Berlin Senate. The architect was able to win over the building senator with his routing from the baroque Kollegienhaus into a subterranean labyrinthine basement with two corridor axes, the continuity axis and the Holocaust axis: In order to get from the old building to the new building, each visitor must descend the stairs into the dark past, wander along the intersecting main axes, retrace the experience of flight, expulsion, imprisonment or exile, and ascend the main staircase to the three-storey new building, which is intersected by empty shafts (2).

On the one hand, this subterranean access to the museum is an integral part of museal temples of education through the history of the Louvre in Paris, but here, against the historical backdrop of the extermination of the Jews, this circuit through excavations in the subsoil gains the effectiveness of a Holocaust subtext, which Libeskind would like to be understood as part of his concept of a “performative” built structure:

“Das Jüdische Museum ist kein gewöhnliches Gebäude. Es ist kein allgemeiner Ausstellungscontainer, sondern ein Bauwerk mit einer eigenen Geschichte. Ursprünglich nannte man es die Jüdische Abteilung des Berlin Museums, eine Bezeichnung, die ich vehement ablehnte. Die jüdischen Bürger Berlins lassen sich nicht in Abteilungen einteilen; sie waren und sind ein lebendiger, pulsierender Teil der Stadt, ihr Erbe ist mit dem städtischen Leben verwoben. Ihre Vernichtung während des Holocausts hat die deutsche Kultur ausgelöscht – als ob ein Großteil der vorangegangenen Kunst, Philosophie, Musik und Literatur aus der Geschichte getilgt worden wäre. Ich glaubte, dass es möglich war, diese Auslöschung wieder ins öffentliche Bewusstsein zu bringen, indem ich ein Gebäude entwarf, das die Geschichte erzählte. Zu jener Zeit wurde ich für diese Idee heftig kritisiert. Bedeutende Kritiker, Historiker und etablierte Architekten wiesen mich ab. (…) Aber ich habe immer daran geglaubt, dass Gebäude durch ihre Proportionen und Materialien, die Art, wie sie mit Licht umgehen, und die Emotionen, die sie wecken, etwas aussagen können.”[3]

Since its opening, Libeskind’s architectural language and spatial formation has been related to expressionist architecture and sculpture, to contemporary architecture and American deconstructivism, to John Hejduk, the New York Five and Peter Eisenman, and less frequently to music, film and performative art. Journalist Janet Street-Porter compared Libeskind to a director who never underestimates his audience: “An hour of your time enjoying this building beats two hours of a Spielberg fantasy any day of the week.” The play with fractured perspective and the surprising change of proportion in the sculptural Imperial War Museum North seems musical to her: “if that building was a song, which one would it be?”[4] For Libeskind, who found architecture through music and drawing, the musical quality of his buildings is more than a reference to the doctrines of proportion in architectural theory:

“Music is very close to how I understand architecture. Both are about proportions, exactness, vibrations, acoustics.”[5]

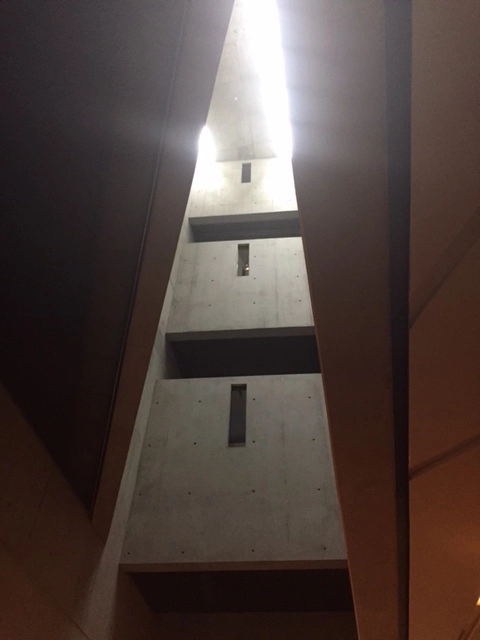

If we start with the architect’s central spatial conception in several of his buildings, the empty spaces with little light or inaccessible shafts of his buildings called “voids” (3), this musical analogy must encompass a postmodern reflection on sound, silence and dissonances of modern compositions: Modern poetry and its timbres, Arnold Schoenberg’s compositions, graphic and painterly abstraction from Paul Klee to Marc Rothko.[6] In a formation of space informed by avant-garde designs and “paper architecture”, it is not a matter of proportional harmony but of constellations full of tensions and dissonances. By understanding resonance not only as a physical fact, but as a sensory-cognitive formative transmission of vibrations, Libeskind was able to considerably increase the polyphonic inherent sound of his buildings. The fact that buildings are not only structures but also sounding bodies was marginalised away from utopian designs between reinforced concrete skeletons and architectural engineering. Libeskind conceives precisely from these edges of architectural sculpture and thus moves the holistic address of all senses through built spaces back to the centre. Using the example of German-Jewish history in Berlin and national war history in Manchester, a conceptual geometry of contrasts and interruptions shines through, playing off the possibilities of concrete against functional tectonic spatial construction. Dissonances, asymmetries and supposedly disproportionate relationships of parts to each other are Libeskind’s preferred means of expression in both museum buildings:

“Es geht nicht darum, die Leute zu schikanieren … Ich möchte, dass sie sich sofort bewusst sind, dass sie sich in einen Spannungszustand begeben”[7].

In the case of the Jewish Museum in Berlin, however, such a spatial experience, which the architect describes as a sensual response to the narrative of his building, is optimally possible only when the building is completely empty: 350,000 visitors came to the opening in spring 2001 and experienced an unusually autonomous formal language as surprising, imaginative and impressive. Critics noted that the furnishings for normal museum use would diminish the auratic effect of the light-shadow modulation and the unexpected asymmetries, and that the ribbon windows borrowed from industrial architecture were completely inadequate for exhibition spaces. Some felt the building was more of a monument than a museum.[8]

The storyline of the permanent exhibition on the cultural and everyday history of Judaism, spread over two floors, in whose exhibition design the architect was no longer involved, could only begin anew through the routing by jumping back in narrative time from 1933-1945 to antiquity on the first floor. This break with the linear storyline, like the radical spatial multiperspectivity of the building, had seemed new at the time. The aesthetics of multiple perspectives make it impossible for exhibition visitors to predict the spatial arrangement. The zigzag line of the floor plan can only be seen from a bird’s eye view: It is reminiscent of lightning and, in designs as the “Line of Fire”, is the beginning of a metaphorical dimension of the acute-angled spaces.[9] In the executed building, this sharply jagged line remains unnoticed: the fragmentation allows only excerpted views of the structure, e.g. from the over 365 windows or into the light wells. Thus, the design supports the insight that there can be many different perspectives and interpretations at the same time in historical narratives by means of opposing axes of vision. Like a broken crystal, the architecture also shows too many views for them to be able to fit together into a manageable, regular arrangement. The Jewish Museum Berlin’s exhibition and education programme in terms of content is committed to this visual diversity and multiperspectivity and has aligned Libeskind’s structural narrative with its collection- and exhibition-related museum narratives. The architect describes the creation of the floor plan by mapping historical sites of Jewish intellectuals and artists on a city map as his poetic access to a past and imagined Jewish city life:

“Ich habe alle Adressen auf einer Karte eingetragen, um meine eigene Matrix zu erstellen, und die Punkte in einem emblematischen Davidstern verbunden, der die Organisation des Museums und die Schrägstriche an der Fassade des Gebäudes bestimmt. Ich habe mich auch an Walter Benjamins Einbahnstraße orientiert … und die städtischen Orte, die er erforscht, als Punkte in meinem Entwurf verwendet.”[10]

According to Libeskind, the threads of life of the Jewish-German Berliners were torn apart between 1933-1945, the continuity of their common history violently shattered: The broken Star of David became the basis of the ground plan line. Lastly, this graphic method of visualising the erased creative Berlin, a projection and graphic transfer, is associated with the unfinished opera Moses und Aron by Arnold Schönberg. The composer, who fled to the USA in 1933, thus took up the Exodus from Egypt and the second commandment of God’s unimageability. In the context of the Jewish Museum’s Holocaust narrative, unrepresentability implies the commandment not to show the horrors of genocide pictorially, i.e. to choose non-representation for ethical reasons. Libeskind’s conception is therefore a “post-memorial” one of the post-born, i.e. it is related to the painfully felt void in the artistic as well as intellectual life of Berlin from the post-war era to the present. The metaphorical dimension of this architecture is suggested by sounds, the reverberation of human footsteps:

„At the end of the second act Moses calls to God, but there is no answer. I thought I could complete the third act with this building, in the reverberation of visitors’ footsteps across a void.”[11]

Resonant architecture thus means for Libeskind, on the one hand, conceptually referring to the specific history and memory at a site, e.g. by mapping lost Jewish persons and addresses. The projects are developed on the basis of a historical-cultural memory; on the other hand, they are interpretations influenced by the examination of utopian architectural designs by avant-garde artists.[12] Thirdly, the effect of the spaces is related to the individual as a resonating body, who can subjectively experience history and memory through the spatial constellations, material language, light and darkness. Although the building is static, it should appear open, dynamic and changeable through perception in the process of movement, so that it can stimulate and sustain the imaginative capacity of the subject and the audience, conceived as part of the social present.

On the light-sound installation res.o.nant at the Jewish Museum Berlin 2017-2019

The Düsseldorf conceptual artist Mischa Kuball returned to the idea of resonant spaces inherent in the conceptual design history of the Jewish Museum for his examination of the architectural situation and the museum narrative in 2017. By inviting contemporary artists to let the spaces created by Libeskind become the starting point for their own temporary installations, the museum’s management wants to programmatically chart a new course, which naturally follows from the museum as a place of the muses (ars) at the Jewish Museum as well.[13] However, instead of once again presenting exhibitions only for sworn museum lovers, the museum is now to be used in a more versatile way than before, not only as a place of remembrance and learning, but also as a human contact zone and space for artistic interventions and performances. Programme director Léontine Mejer-van Mensch represents approaches of the institution-critical New Museology and follows Fiona Cameron’s idea of a Liquid Museum in reference to Zygmund Baumann’s analysis of liquid modernity as a social permanent dynamic. Libeskind’s underlying connection to the displaced and lost Berliners must be constantly supplemented by close references to social discourses and direct relevance for today’s Berliners, and the focus on historical lore and collection objects must be reconsidered and supplemented by other formats and offerings. The goal is a place that, in the face of dystopian features of global politics, positions itself more resolutely as a “public space” for encounter, tolerance and social integration. The relevance of the museum’s work is thus not limited to the usual cultural education mandate, but is intended to help develop new narratives of German immigration society more emphatically with both long-established and newly arrived Berliners. Libeskind’s crystalline multiperspectivity, updated programmes for permanent and thematic exhibitions, and a turn towards the contemporary and the immediate urban neighbourhood are facets of the new orientation planned for the coming years.[14] The collaboration with artists from Israel and Germany, who were previously only represented with selected works in curated temporary exhibitions, can also be seen as a vanguard of this opening to new themes and visitor groups. Now the collaboration is to include many new partners of the museum and the relevance is to be expanded beyond the touristic and educational significance.

Archive photograph Jewish Museum Berlin

On the occasion of the comprehensive redesign of the permanent exhibition, temporary projects became possible again for the first time since 2002 in the vacated Education Centre with adjacent exhibition area in the basement. All exhibition-related fixtures were removed except for the lighting (4). With conceptual artist Mischa Kuball, the plan to incorporate Libeskind’s museum architecture into the project was realised between autumn 2017 and autumn 2019: a site-specific walk-in installation occupying over 350 sqm of the vacated Void Tower facing Lindenstrasse and its connection to the entrance stairwell. Like all of the artist’s projects, it is not only conceived as a temporary intervention in existing spatial constellations, but only actually becomes complete through the presence and reaction of visitors to the basement labyrinth. Alongside the site-specificity, which includes knowledge of the architectural plans and ideas, comes the relational component: the matrix, similar to the design history of museum building, consists of ideas, people (here the museum audience) and the history and significance of the site (here the architecture with its specifications). Libeskind’s knowledge of utopian “Bauhaus ideas” through his architectural studies is a common feature with Kuball’s conceptual exploration of the reverberations of Bauhaus design doctrines in art: both play with the all-too-familiar elementary grammar and aesthetics from a view of design shaped by personal educational experiences. Exposed concrete, glass and metal are the means of one, light, form, colour and mirror the means of the other. In both works, post-minimalist reduction of means is not an end in itself, but creates the space for educational processes based on non-linguistic experience and recognition. In both artistic conceptions, a modernist aesthetics of the sublime is critically reflected upon after the crisis of representation. The contrasting play of the non-identical in Libeskind’s building forms the antithesis to the monotony of a field of stelae such as the Topography of Terror. If Minimal Art brought the process of perception through movement around abstract objects to the fore, Libeskind and Kuball can start from this processual formation of space and form and include processes of bodily resonance in their processual spatial concepts. Both artists challenge the idea that physical, geometric space is a kind of container that is unchanging in its dimensions. Through the duration of movement through the space and through light and sound, the geometric space is also a performative space at all times. For this expanded spatial aesthetic influenced by architectural psychology and theories of perception, human resonating bodies in motion are needed in both cases. Secondly, there is not the one objective space that everyone sees, but the space is constantly produced in the autopoietic feedback loop and, unlike physical space, is “atmospheric”. We do not just visually scan an inclined concrete surface because perceiving is more than a purely cognitive process that constantly calculates and regulates our own positioning in relation. Our sense of balance compensates for uneven spatial coordinates and allows us to move forward safely on rising floor ramps or in sparsely lit environments. So from a physical, bodily physiological, anthropological and sociological point of view, resonance is always relational. In every installation experience, the step from relationality to environmentality is individual; the sensory reaction and cognitive evaluation of what is perceived as “unstable”, “open”, “wide” or “uncanny” is equally subjective. In the Jewish Museum, the Holocaust Tower, as a symbolic dead end, has no function for the museum operation, yet it is precisely because of its “uncanny” atmosphere that it is a meaningful link in the museum narrative mentioned at the beginning. The voids, too, were often perceived as “uncanny”, insofar as they were allowed to be entered at all. This bodily discomfort is the result of an interplay of “environmental constellations”, lighting conditions and vivid individual imagination. Gernot Böhme defines atmospheres as subjective spaces that are created by the “ecstasies” of things, people and constellations in a reactive triangle as “spheres of presence” of something.[15] Both Libeskind and Kuball assign viewers an active role in the production of space. Constellations and materiality allow forms, images and atmospheres to become present to the sensing subject: The museum and the installation thus offer dense atmospheres that elude rational, deliberative thinking and entangle us in bodily sensation.

An installation that is designed as an intervention in “environmental constellations” does not correspond to the usual understanding of installation art in the art business of museums, exhibition houses and galleries. An “intervention” is derived from the action, the intervention in given things or a performance by the artist: either in front of or with the audience or as acting for the film or video camera as mediator of this action. The interventions that Kuball has been carrying out for many years in found constellations between public and private spaces elude the usual art-critical classifications as conceptual, space-related and space-creating projects. They are installations informed by performative art, time-based art and minimalist situations, without repeating previous concepts. The processes set in motion by intervening, changing and communicating connections of the previously unconnected aim beyond the boundaries of the presentation site and – similar to photography – need a temporal development in the field of the social in addition to the instantaneous. Since the 1990s, Kuball has carried out a series of such interventions in or on buildings in urban spaces, using projections and light reflections to draw lines, colour surfaces and light spaces. Kuball illuminated the former Jewish synagogue of Stommeln near Cologne, whose congregation was dissolved in 1933, in the form of Refraction House (1994), glaringly glistening light into the nocturnal surroundings. All viewers of this illumination were bathed in painfully blinding light and involuntarily became the medium for shadow cracks. This was certainly the most radical intervention among the light works dealing with German history and Jewish fates in concrete places. The 33,000 lumen light shone at night on residential buildings opposite, fragmenting the surrounding space into errant drop shadows and flashes of light.[16] Light as a medium and artistic material is at the centre of perception, recognition, remembering and feeling in many of Kuball’s works, exploring the close relationship between projection, optics, perspective on the one hand and stimulation of imagination and reflection on the other.

Artists engaged in shaping ephemeral light-shadow spaces or light forms at the Jewish Museum Berlin need courage, for they are competing with Libeskind’s “graphic” light direction of pointed triangles and bold diagonals (5). The entrance shaft with the steep descent of the stairs leads into the tunnel-like corridors to the first void shaft, which can be entered via an exhibition area.[17] If one looks up three storeys from this shaft to the skylight opening, on sunny days the impression of brightly shining, trapezoidal light forms in the upper third of the room height emerges (6). The exposed concrete is preserved here unrendered, while the white walls and suspended ceiling of the exhibition area were left in place during the deconstruction of the basement exhibition space in this void shaft, which is subdivided into three connected rooms, initiated in 2017. [18]

Kuball’s dialogue with Libeskind’s performative architecture begins with audibly clacking, rotating projectors on the walls of the winding stairwell shaft. Museum visitors are illuminated by rotating spotlights: the timing makes this process automatic: everyone in their privacy experiences an initiation and becomes an element of the public. For Kuball, this relevant public sphere is something that must first emerge with the collection of people in this place in changing constellations.[19] The light barrier as an entrance to the installation is followed by the confrontation with one’s own horizontally cut mirror image at the fork of the two subterranean museum corridors. Three kinetic, strongly illuminated modulators consisting of two human-height mirror elements rotating in opposite directions by 360 degrees were positioned: one at the intersection of the two main axes, one in the void shaft with light and sound, and the last in the elongated exhibition space of the basement, opposite a recessed collection showcase with tinted glass (7).

At the entrance to the rising exhibition space, the positioning thus directs the visitor from the corridor into the installation, which is spread over three interconnected rooms, through an adjacent lighting chamber that lights up deep red, into the void shaft enlivened with projections and sound, and back again to the mouth of the corridor. The three-step in this sequence is not compulsory, but increases the intensity of the sensory experience in the light-sound installation. The first experience concerns thermoreception: it is cooler in the cellar. During my visit, visitors who expected a continuation of the museum narrative “The Shoa in individual fates” looked questioningly at Libeskind’s minimalist object showcase, whose metre-long glass surface becomes a projection surface for changing colour and form plays through sudden reflections of the two mirror rotators and red light falling in from the side. Depending on the location, the screen glows blue to light grey or shows abstract-looking light painting. The bodies passing by also draw themselves into the process of image-making, which leads to frequent photographing and filming with the smartphone. The visual impressions, however, as is typical of Kuball’s performative light plays, are passing phenomena of our perception and imagination, whose meaning lies in the experienced suddenness rather than in the documentation to be viewed. One must not want to own them, only experience them individually: therein, as in so many aspects of this installation shown uniquely until September 2019, lies a subtle critique and connection to the unrepeatable performance. In the acute-angled room next door, the ceiling height is manageable, as it is in the exhibition space, as long as you can still orient yourself enough about the room’s dimensions in the darkness: Without warning, the whole room begins to glow yellow-orange to deep red through three high-voltage lights placed in the corners (8,9).

As soon as you get the impression that you are surrounded by red in all directions, a firework of stroboscopic flashes is unleashed on your senses. The flashes are followed by darkness again. The surprising effect of this sensory overload is that the human contours of museum visitors strolling by dance as afterimages on the retina and the perceived moments are subsequently diffusely mixed. The temporal synchronisation of all the projecting, rotating, fragmenting and sound-transmitting apparatuses together create an eventful passage through light, shadow, colour and (sound) atmosphere. Meanwhile, in the three-storey and angular Void concrete shaft, two slide projectors supplemented with loudspeakers rotate in a circle. Kuball breaks the rugged grandeur of the view upwards with his circling light projection on the walls, ceiling and floor (10). As at the entrance, the cone of light wanders so low that people can be caught by it and illuminated if they like. The refraction of the light rays creates a flowing change from circle to rectangle, with the skylight at a height of 24 metres being superimposed once each by the projection of one of Libeskind’s three floor plans. The abstraction of the room is thus traced on supporting elements and on the floor by the continuous loop of projected light surfaces. The light effects of all three rooms work together through the wall openings as “apertures” and create ephemeral geometric colour surfaces in continuous, “film-like” movement by shining into adjacent areas. This dialogical and repetitive process succeeds in reversing the effect of Libeskind’s sublime to uncanny gesture of abstraction: the abstract of the spatial constellations is related to the point of view and the figure of the person in the space. Visitors and light forms meet, images of the human body are split by reflections. The stroboscopic flash of light prevents one from maintaining a fixed point of view and causes an intensification of the experience of colour space. One can understand this path into negative representation in terms of media theory, from the flash of light of the photo camera, or also as a reflection of Jewish cultural tradition. The curatorial direction welcomed the choice of an artist who does not exhibit his own images in the museum, but practices an art without images.[20]

res.o.nant is a virtual space created by light, sound, reflectors and resonances. Through light projections and sound installations, the fixed coordinates of Euclidean space can be effortlessly overcome and overdrawn by imaginary or no longer perspective perceptual spaces of hearing, seeing and feeling. Every space-sound installation enables an “atmospheric” intensity and can stimulate open, situational perception, as Stockhausen already emphasised in his remarks on electronic music.[21] Mischa Kuball’s Open Call to musicians led to the migration of found sound clips (skits) by professional and amateur composers of musical collages into the museum space. The artist’s invitation to send him sounds lasting exactly 60 seconds corresponds to a participatory approach and at the same time ties in with image trouvés and resampling. The timing of the light projections and mirror rotations correspond to the minute cycle, so that the sound collage was coordinated with it: 60 seconds of sound alternates with 30 seconds of silence. The takeover of all the sounds broadcast corresponds to Kuball’s concept of equal participation of all contributors and ensures a constant variation of the sound component of the installation. The number of clips continues to grow so that the projector-mounted loudspeakers now transmit the sound clips stereophonically, from two sides, for 20 seconds with pauses of 10 seconds. The abrupt change of violin sounds and electric sounds is perceived as atmospheric reinforcement in the light installation, although some of the sound constellations were created independently of the project. Titles appearing on displays such as “Kristallnacht” (composer John Zorn) or “never again” can evoke associations with war and genocide, while titles such as “Echoes of the Void” (Witzhum, 2017), “Abyss”, “Sein” or “Spazio” can act as rhythmic sequencing of the spatial impression. The admission of even disturbing, intrusive or popular melodic fragments is based on the conceptual extension of modern ideas about “abstract hearing”: Heidegger’s philosophical conception of a pure perception, aísthesis, and of “pure noise” apart from linguistic-cultural representations was guided by his influential idea of the origin of the work of art: “In order to hear a pure noise, we must listen away from things, withdraw our ear from them. “[22] The capacity for abstraction demanded here refers to the essence of perception, the omission of attribution of meaning. Morton Feldman still states during his collaboration with John Cage that the most difficult thing about aesthetic experience, e.g. an artistic performance, is to maintain this “original” perception, assumed a priori by Heidegger, over a longer temporal duration against acting sensual and especially cognitive impulses.[23]

When sounds gradually build up, this happens in a similar way to light projections deforming from one form into the next: both build up into light or sound forms at intervals of time and become more present to our visual and auditory perception stage by stage. Although visitors to the exhibition at the Jewish Museum will quickly discover the sources of the effects during their passage through Kuball’s resonance rooms – the artist always visibly exhibits his apparatus – the majority of them remain standing in front of the projection surfaces, looking and listening spellbound. While the endless loop of circles that turn into squares is on the one hand transparent as a game with basic geometric-architectural forms and perspective, the listener of the sound clips cannot discern any composed connection between image and sound, even if he perseveres for a longer time: Comparable to John Cage’s random music, it is impossible to guess what will come next. In their essay After Modernism, Cage and Feldman emphasised that sounds that want to be nothing more than sounds leave the listener with an experience of hearing without association of ideas.[24] The mere swelling and falling of sounds in space causes a more intense perception and holds us captive for a while, because listening, like visual experience, is initially a self-referential experience of time: sound is time, being is time. Kuball names intensified perception, beyond superficial techno-sublimity or neurophysiological overstimulation, as a possible experience: space and body meet in the brief flash of a resonance. The installation can also be experienced as an echo chamber for the footsteps and voices of museum visitors in empty spaces and thus close to Libeskind’s idea mentioned at the beginning, but younger generations certainly lack this subjective reference to the traumas of the Second Generation of Jewish Americans. The installation involves museum visitors in Libeskind’s performative spaces and conveys their unusual constellations. In addition, as in many of his public prepositions, Kuball is concerned with the opening up and accessibility of spaces and places through light, (signal) transmission and communication with a group of addressees thought to extend beyond the interested museum public. The artistic claim to publicise spaces and to create a democratic (assembly) public together with as many as possible is thus considerably extended into the social spaces of today’s Berlin. The surrounding space of the JMB became the “arena” of the “public” passing by at random on the chosen action days through reflections from the interior to the exterior space that were part of the project. [25] Kuball’s response to the specific situation of the fortress-like enclosed JMB grounds are thus interventions in public space at neuralgic points in the immediately adjacent neighbourhood. Since September 2018, further light projections and sound installations have taken place on the forecourt of the Kollegiengebäude and on Oranienstrasse on specific dates. The determination of the position resulted from Libeskind’s conceptual floor plan of the museum building with the mapped memory points of a collective memory of lost inhabitants. The Void floor plan lines of the basement gave direction and dimension. They were extended from the interior of the Libeskind building into the Kreuzberg neighbourhood and projected with light into the immediate vicinity of the museum. In the period since res.o.nant opened, the collection of sound clips grew from 40 to over 220. In autumn 2018, the sounds penetrated the surrounding streets and residential areas around the JMB from the basement via a highlighted area in front of the Kollegiengebäude equipped with loudspeakers. In parallel, existing billboards in Oranienstrasse with excerpts from Paul Celan’s poem Oranienstrasse 1 and large-format photographs of the res.o.nant audience had been appropriated for this intervention. The poet Celan and the tortured journalist Carl von Ossietzky appear as two lifelines broken by the Nazi dictatorship, which became visible through their embedding in the media-well-connected interaction project. In front of the billboards, the floor plan of a void with the Twitter link to the project was drawn on the pavement: Everyone was invited to leave comments on the intervention at this location or to write them on the posters. The role of the artist is that of an agent who enables the comparison then/now, power/powerlessness, homogenisation/diversity, etc. through spotlights and snapshots and encourages understanding about the sore points of the city and democratic participation in it. In 2000, Kuball had for the first time prepared a public speaker stage for the citizens in Halle an der Saale, which was connected to the Städtische Galerie Moritzburg, the inviting organisation, through light projections. res.o.nant has a similar relationship with the host JMB, giving a uniquely long development period of almost 2 years until September 2019 and reaching a very broad and culturally diverse audience in a very short time. As a platform, the museum offers continuity and publicity, which is all the more important due to the fleeting nature of today’s internet communication, in order to open up possibilities for the concept to have an impact beyond the institutional boundaries of the museum, beyond the mere presentation in the exhibition context.

Legal, technical and organisational hurdles already had to be overcome when moving the performance from the protected space for education to the surroundings of the Jewish Museum. Above how many decibels is art in an urban space considered noise? The strict security requirements for the museum made larger, uncontrolled crowds as a symbol of freedom of art and assembly equally problematic. While the live musical performance by invited sound artists in the installation was deemed unobjectionable, the addressing of citizens via billboards gave rise to concern, given simmering anti-Israeli sentiment following recent military actions by the Israeli leadership, as to whether this would not present new fodder for enemy thinking. For the artist, these interventions are an integral part of his project, not at all a kind of accompanying educational framework programme with the character of a spectacle. Of course, in view of the lived realities between exclusion and inclusion, it would be ideal if the activities were not only initiated by artists and if the neuralgic points were not only historical but also current problem zones. To what extent the museum as a public place of encounter and exchange could actually compensate for the dwindling number of non-interested publics is difficult to assess within the framework of programmatic cultural events. Kuball’s approach is intended to make us aware that the spaces of political and cultural public spheres must be maintained and renewed through free communication and constant negotiation: they are neither static nor permanently guaranteed constellations, always to be protected anew against encroachment and to be founded on a capacity for reflection that is ready for dialogue.

The idea of the multi-reflector light space underlying the project has a prehistory in the artistic experimental spaces of the 20th century. It ranges from Walter Ruttmann’s film Symphony of the Big City and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s Light-Space Modulator to the light ballets of the ZERO artists, from Bruce Nauman’s Green Corridor to immersive coloured light spaces. As an installation in a museum space, res.o.nant is both site-specific and situational, so it delved deeper into Libeskind’s idea of the museum and his performative understanding of space. Secondly, points of contact between Libeskind’s radical edge-of-order geometry and the malleability of his material concrete with Kuball’s projection art and the malleability of his material light were shown without assuming similar intentions of the artists. Finally, the relationship to temporally stratified memory and social spaces in the city of Berlin was placed in relation to each other in the two artistic projects. If, on the one hand, Kuball’s installation can be interpreted as a further drawing of an imaginary space into an architectural (building) body and into human resonating bodies, the cross-border markings, projections and sound performances in the public space surrounding the city district present themselves as a clearly institution-critical variant of a hybrid new public art. In contrast to performative action art, however, the artist quickly withdraws from the (partial) public sphere marked by him, in order to leave the field to the chance of the processes and the “audience” that is difficult to control outside the museum space. In relation to Berlin’s memory and social spaces in and around the Jewish Museum Berlin, the project of the resonance space is therefore also related to contemporary socio-cultural conditions and thus not only site-specific, but site-responsive. Libeskind and Kuball meet in the conviction that aesthetic imagination and sensitivity can also change the ethical imagination and conviction of a society through resonance. Subject-centred modern reception aesthetics remained trapped in the cycle between alienation and affirmation of the ego in its relationship to the “world”, to its objects, images or constellations, and rarely opened up seeing, thinking or feeling differently. By expanding Libeskind’s musical-architectural resonance with the contemporary sociological dimension and stimulating resonance phenomena as an almost culture- and norm-free educational process of pure aìsthesís, Kuball overcomes the self-referentiality of the viewer before the image. The opening of the hermetically sealed museum space can also be interpreted symbolically as a reference to the social significance of resonances in contemporary theories of participation. Through res.o.nant, the “uncanny” voids are released from their embedding in the museum narrative and transformed as a resonance space for contemporary processes of communication and education. Unfortunately, the reactions of the JMB’s international visitors to the temporary installation and its spillover into the surrounding urban space were not recorded over the course of the project. But this does not diminish the conceptual and intellectual ambition of this complex project, which differs significantly in its scope from merely space-related light-sound installations due to its processual and participatory components. The openness to interpretation and ambivalence of the voids ultimately also apply to Kuball’s conceptual engagement with Libeskind’s metaphorical spaces in the JMB: “What is important is the experience you get from it. The interpretation is open.”[26]

_______________

[1] Daniel Libeskind’s architectural model of this project is lined with text pages from the Bible and is now in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art New York.

[2] Zur Relevanz postmemorialer Erinnerungskultur der 1990er Jahre vgl. Silke Walther, “Imagined Communities in Contemporary Holocaust Exhibitions”,, Konferenzband, European National Museums and a difficult Past” hrsg. von Dominique Poulot/Felicity Bodenstein/José M.L. Guiral, Linköping University Press 2012 [http://www.ep.liu.se/ecp/article.asp?issue=082&article=006&volume=]

[3] Daniel Libeskind, Edge of Order, New York 2018, 232

[4] Janet Street-Porter, “Editor-At-Large: Movie director or architect?” Column on the opening of the Imperial War Museum North, in: The Independent, 30.06.2002

[5] “Music is close to how I understand architecture, Daniel Libeskind in interview with Sandra Trauner, NMZ Online, 28.12.2015 [last accessed 31.03.2019].

[6] “Void Spaces”, incisions in a spatial continuum are defining design elements alongside the Jewish Museum in the Felix Nussbaum Museum and in Libeskind’s extension for the Victoria & Albert Museum.

[7] Daniel Libeskind”, Interview mit Jason Cowley, The Prospect Magazine, 20.02.2003 [https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/magazine/daniellibeskind, letzter Zugriff 3.4.2019]

[8] “the exhibition spaces are on the one hand totally inadequate … (…) But … the possibilities inherent in the Libeskind building are amazing”, kommentiert K. Gorbey am 23.5.2001, zit. N. Susanne Reids Rezension des JMB, in: Virtual Library Museen Online [ http://www.historisches-centrum.de/aus-rez/reid/01-1.htm]

[9] Elke Dorner, Das jüdische Museum 3. Aufl. Berlin 2006, 16.

[10] Libeskind, Edge of Order, New York 2018, 232

[11] Libeskind, Edge of Order, New York 2018, 233

[12] “Innovative Ideas always win through”, Lasse Ole Hempel im Gespräch mit Daniel Libekind, in: Pulse Movements in Architecture, Nr. 01,01, 2013, hrsg. von LPR Architects [https://www.busch-jaeger.de/uploads/tx_bjeprospekte/ABB_pulse_magazine_2013_1.pdf]

[13] Berlin’s first Jewish Museum presented works of modern painting, including Max Liebermann’s, from 1933. Individual works from the art collection confiscated in 1938 resurfaced after the Second World War in the former cellars of the Reich Ministry of Culture and were given to the Bezalel National Museum Jerusalem. By integrating works of contemporary art and photography into the collection and the exhibition programme, the Jewish Museum Berlin Foundation is therefore continuing the tradition of the Jewish Museum, which was destroyed in 1938. I thank curator Gregor Lersch for insights into the exhibition history of the JMB.

[14] „Das jüdische Museum Berlin das ich mir erträume“, L. Mejer van Mensch, Vortrag Educating Curating Managing ECM Diskurse, Nr. 31, Universität für Angewandte Künste Wien 2017 [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gN-Tt7uz2VY]

[15] Gernot Böhme, Atmosphere, Essays on the New Aesthetics, Frankfurt a.M. 1995

[16] Armin Zweite, Refraction House, in: Florian Matzner (Hrsg.), Mischa Kuball, Projekte 1980-2007, Ostfildern-Ruit 2007,59-81

[17] Libeskind originally planned for four voids cutting through the main structure to shape the silhouette of the museum as prominent towers, but for cost reasons this first light shaft was connected underground to the old building and only the Holocaust Tower was left completely exposed.

[18] This not entirely realisable exposure of the shell condition is part of the artistic project plan for the installation res.o.nant and will again have to make way for exhibition-specific space requirements and lighting from October 2019.

[19] Vgl. Vanessa Joan Müller (Hrsg.), Mischa Kuball, Public Prepositions, Berlin 2015

[20] Gespräch der Autorin mit Gregor Lersch im JMB, Januar 2019.

arlheinz Stockhausen, Texte zur elektronischen und instrumentalen Musik, Cologne 1963.

[22] Martin Heidegger, “Der Ursprung des Kunstwerkes”(1935/36), in: Martin Heidegger, Holzwege, ed. by Friedrich W. von Hermann, 9th ed. Frankfurt/Main 2015, 1-66

[23] Morton Feldman, After Modernism (1971), first published in Art in America, LIX, No. 6, new edition German translation edited by Walter Zimmermann, Kerpen 1985, 95-108

[24] Feldman, After Modernism, ibid. (note 18).

[25] Vanessa Joan Müller (ed.), Mischa Kuball: Public Prepositions, Berlin 2015, 11-15; Paul Celan, Todesfuge. Illustrated edition with papercuts by Mischa Kuball, New York 1984.

[26] Libeskind, quoted from the text for the museum tour of the basement of the Jewish Museum, January 2019, n.d. A.

res·o·nant

A light and sound installation by Mischa Kuball at the Jewish Museum Berlin

WHEN? 17 November 2017 to 1 September 2019, open daily from 10am-8pm (closed 30/09, 01/10, 09/10, 16/11 and 24/12/2019).

WHERE? Jewish Museum Berlin, Lindenstraße 9-14, 10969 Berlin-Kreuzberg, in the Libeskind Building UG, Rafael Roth Gallery

ENTRY? with the museum ticket (8 EUR, reduced 3 EUR)

About the author:

Silke Walther studied art history, English and contemporary history in Bochum, journalistic training and work as an online editor, doctorate on post-classical architectural aesthetics at the University of Stuttgart, research assistant for modern and contemporary art history in Karlsruhe, Bochum and Kiel, since 2005 freelance work on exhibitions and exhibition-related publications on architecture and theory, contemporary art and photography, guest lectureships and teaching positions at design and art colleges, most recently substitute professor at the HfG Karlsruhe, lives and works in Bochum.