There are countless ways to represent the world, and all are of equal importance. Simply because, as J.Z.Young said, “the brain of each of us creates his or her world” (Andre Masson). Therefore, the artist’s job is not to paint things “as they are”-that phrase is indeed meaningless-but to make us believe that they are as he paints them. Every truly creative artist offers us a new picture of the world and convinces us that this is reality. And by convincing us, he adds his vision to our habits of seeing the world around us. But the artist, before he develops his vision, himself has habits of seeing that he has inherited from other artists. Because these habits are deeply rooted, he can only modify the visions of others – usually contemporary artists or even old masters to whom he is most attracted. This interplay of new and already existing visions creates a living process of development.

Abb. oben: © Lili Lasutra

He who gives himself over to poetic enthusiasm is a god. He who surrenders to thought is a beggar.

Andre Masson

The fact that there is nothing to learn in painting shines through in philosophical circles

(since Plato’s verdict against art), even if for other reasons artist Lili Lasutra presupposes this for her assertion. But if this is so, why say and write things about it that only confirm it? The answer emerges in the question: because the relationship between painting and viewer is not theoretical for Lili Lasutra.

The self-evident primacy of theoretical behavior leads the viewer to believe that moments of purely aesthetic pleasure in the vicinity of the paintings are enough. But the non-understanding of images has a different dimension than pure aesthetics admit; it is precisely this that reveals the inexhaustible. The non-understanding can be of such a kind that it is worthwhile to dwell on it, only for this reason does it changes the “language form” now and then. Accumulated impressions captured in the form of small “notes”, in random photographs, small writings for themselves. On this lies the tone: since after notes follow the work. This is the reason why there is no doctrinally formulated goal. It is about directing to certain experiences of the artistic work itself. And one of the first conditions of artistic work in the present is that it takes place in a fundamentally different space than in tradition.

Lilli Lasutra’s interest in archaeology, ancient cultural legacies, and mythology as such are subject to changes related to her experiences in art.

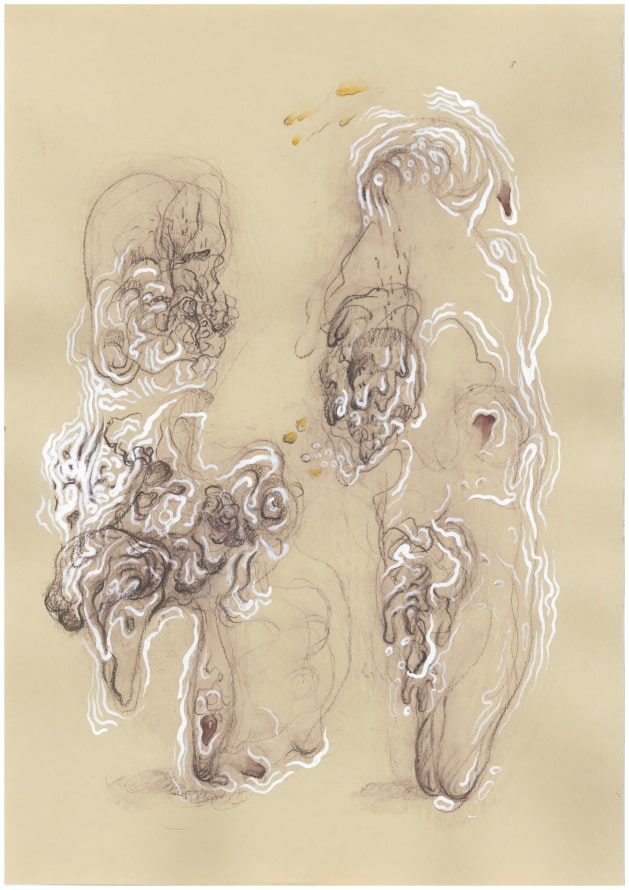

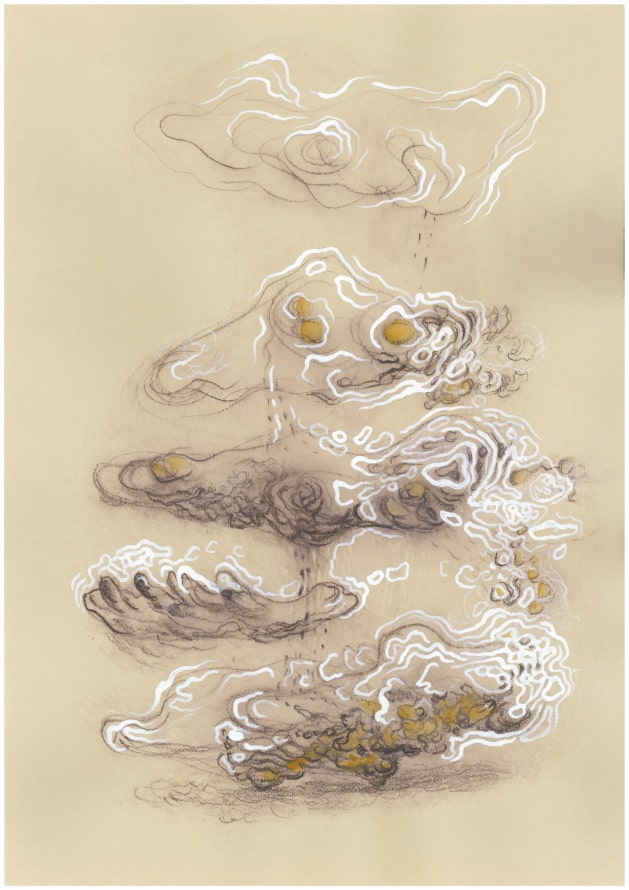

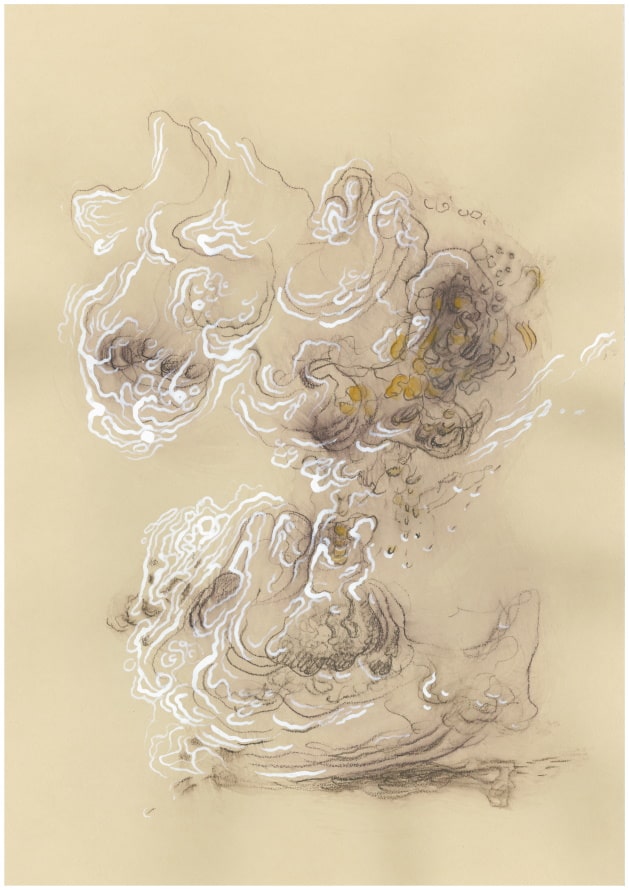

Since it is a matter of drawings, among other things, one has to stick to the lines – at first, anyway. But it is not clear in what way this can be done, because the lines do not open up a precise representation of a subject. They move freely and unconstrained and it is precisely this movement of their own that dominates and appears here as an independent element of drawing.

The features of the lines are neither bound to objects nor are they mere self-expression. Rather, they run in such a way that the surface is rythmised at the same time.

Lines in Lili’s work are unforced, and as she describes the process, it begins with lines of all kinds, the line serving as a trigger. But if you stick to line as a trigger and think you understand it, you are left with illustration, because the lines always bear a resemblance to something.

The diverse lines are not to be understood. Otherwise, one could understand why one later acts in a certain way. However, this particular way of acting is unpredictable, it can never be understood: it always remains with the “technical imagination”.

Lili says: I have long searched for a name for this unpredictability of one’s actions and have only ever found the same words for it: technical imagination. The technical imagination is the instinct that works beyond the laws and thus throws the subject back on the nervous system with the force of nature.

The goal in Lili’s works always goes beyond the examination of the function of the image; what is decisive is the imagination, the look inside. “Seeing is subject to new conditions and with it the production of the surrealist artist who follows the inner voice, the vision, the hallucination, the dream”(Andre Masson). In the 20th century, tendencies developed, especially in sculpture, which is described as organic. The forms appear to have grown organoid and evoke associations with vegetal forms. Since 1900, the organic has formed an antipol to the movements of constructivism, functionalism, and futurism, which were dominated by technical and machine-like “subjects”. Appearing only sporadically at the beginning of the 21st century, the organic form shows itself as a reference to a natural life as opposed to the constructed, artificially assembled.

According to Jürgen Fitschen, the term “organic”, where it is not used in a medical or technical sense, means “belonging to animate nature or, in a figurative sense, in art, representing such nature or linking up with it. The term organic form is, in fact, the designation for a form to which various sculptors, painters, graphic artists and later also architects and product designers adhered in different times, sometimes belonging to this artistic direction, sometimes to that one.”

Characteristic organic forms are swelling figures or objects whose contours emerge in a flowing alternation of concave and convex curves. They appear like primordial forms that grow out of themselves, like “volumes of a body that seem to turn inside out”, symbolising emergence and flourishing the living. The modulation of organic forms extends to the hollowing out of bodies and objects, while also working with holes and recesses in the sculptural forms.

,,Seen from the outside, our time – in contrast to the ‘order’ of the last century – can also be described with one word: chaos. The greatest contradictions, the most opposing assertions, the negation of the whole in favor of the individual, the overturning of the familiar and attempts to immediately rebuild what has been overturned, the clash of the most diverse goals form an atmosphere that leads contemporary man to despair and a seemingly unprecedented confusion”.

Wasily Kandinsky

In his surrealist manifesto of 1924, Andre Breton formulated automatism as the new, pioneering method and indispensable source of inspiration. Andre Masson probably became the most important representative of this theory, as he not least overcame the set limits of surrealism and “the dead-end of simple surrealist symbols”. Organic forms and bodies emerge in Lili’s drawings that are in constant metamorphosis between figuration and abstraction. But what are the different painterly approaches of automatism and abstraction that have persisted into the present? Why did the need arise to break it? In what do the two principles converge and what develops from the theory of automatism? The focus is on the historical background and the painterly-technical procedures of the two theories. The questions of painting without an object, however, were not only the questions of 20th-century painting. Rather, the question remains topical in our present day.

One can already say that the series “Jeux Esprit Automatique” arose from a very spontaneous decision, but there were other reasons for it. But it is necessary to go back a few years in Lili’s creative phase. At the end of 2013, Lili had already begun to devote herself to “automatic” drawings, but it was only later that the attempt at automatism became more and more evident in her works.

Lili believed that automatism, that is, the unconscious, the unplanned, was the real thing. In this sense, Lili began to deal more intensively with automatic drawings. Werner Spies describes in his essay how an “automatic” drawing is created: “Speed serves the artist to overcome inhibition, to reduce the conscious working process, and thus to express unconscious moods. The hand moves freely across the page. In the beginning, it moves in the middle of the drawing sheet. Then the drawing expands, expands towards the edges.”

What sounds like some kind of instruction here, however, is meant to be executed quickly and spontaneously. At least that is the idea. After a few years of trying automatism, Lili also wants to create paintings, or rather oil paintings, with this technique or process. But this quickly presents her with some difficulties, because oil paint has a different behavior than ink, with which she used to make automatic drawings. Lili herself says the following: “Necessity forced itself on me when I became aware of the gap between my drawings and my oil paintings – the gap between the spontaneity and rapid execution of the former and the fatal reflection in the latter”.

In addition, the new colorfulness brings other aspects into the paintings, which Lili did not have to consider in the “automatic drawings”, as these were made almost exclusively with ink.

Nevertheless, as in the ink drawings, the appearance, the emergence of the figurative was brought out and the heterodox image found its conclusion thanks to a brushstroke or sometimes a spot of pure color. Insinuating. ” I first have a sensation of colored rhythms. Represented with paint, these rhythms may have their origin in what I have seen externally, but I know nothing about it. Suddenly I feel filled with a rythmic color. I first note this down, directly on the paper. Then I examine the spots that have arisen, and this continues with these colored areas. I examine it. Why? Because it suggests to me the color, that’s all. The movement of the color itself.”

If you look at Lili’s statement more closely, it seems as if automatism also holds here. Nothing seems planned, deliberately considered, or prepared – in other words, a perfect example of an automatic painting. But Lili herself contradicts here, because ” everything I paint refers to what I have seen, experienced, everything I have become aware of. If nothing is purely plastic, nothing is purely imaginary either: my allegories, my themes draw their substance from the event, from the physical environment in which I live “.

In all, Lili has succeeded in inscribing her works with individual handwriting, which is characterized by an expressive visual style, the play with “narrative and genre conventions” and intermedial set pieces, and not least by her method of presentation.

Aim – to highlight the characteristic aesthetics that distinguish Lili as an auteur in her oeuvre. In doing so, the specific and typical features of Lili’s pictorial worlds will be worked out on the level of content as well as on the formal and stylistic level, and the function of the means of staging will be explained. In this context, we will also look at Lili’s resulting handling of artistic orientation patterns and traditional values.

Text: Irakli Megre, Curator