The Bourse de Commerce is currently presenting the exhibition “Corps et âmes”, showcasing around one hundred works from the Pinault Collection in a reflection on representations of the body in contemporary art. From Auguste Rodin to Duane Hanson, Georg Baselitz to Ana Mendieta, David Hammons to Marlene Dumas, and Arthur Jafa to Ali Cherri, some forty artists use painting, sculpture, photography, video, and drawing to explore the intricate relationships between body and soul.

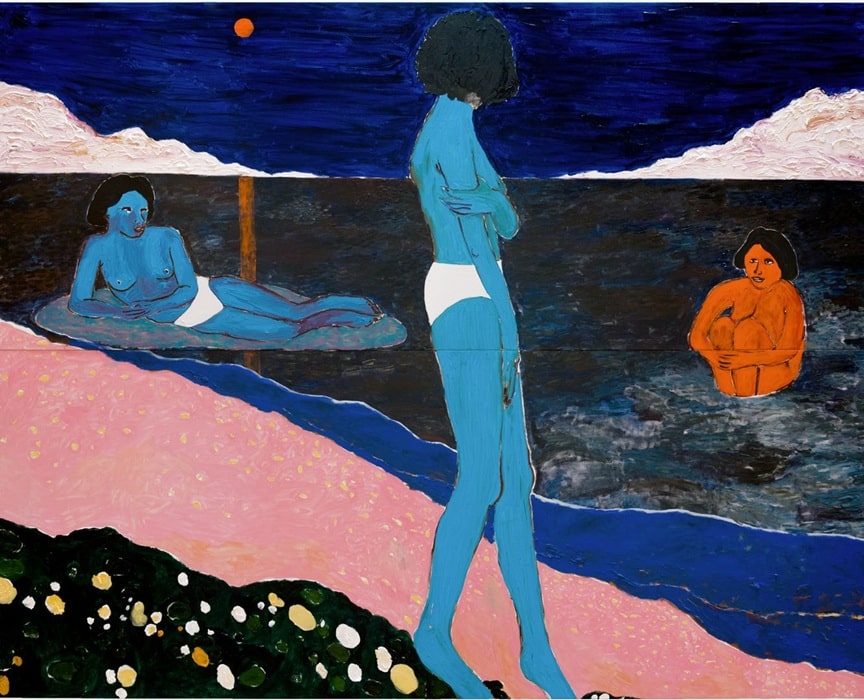

Image above: Gideon Appah, The Woman Bathing, 2021, oil, acrylic on canvas, diptych, 120 × 300 cm (each panel). Pinault Collection. © Gideon Appah. Courtesy of the artist and Venus Over Manhattan.

“In the generative curves of the Bourse de Commerce, as an echo of the rondo of bodies that populate the vast, painted panorama encircling the building’s glass dome, the exhibition ‘Corps et âmes’ explores the significance of the body in contemporary thought through the works of some forty artists in the Pinault Collection. Freed from all mimetic constraints, the body—whether photographed, sculpted, drawn, filmed, or painted—does not cease to reinvent itself, thereby granting art an essential organic quality that allows it, like an umbilical cord, to take the pulse of the human body and soul. Art seizes the energies and vital flows of our thoughts and inner lives to create a socially committed, humanist experience of otherness. Forms metamorphose, returning to figuration or freeing themselves from it, to grasp, hold on to, and allow the soul and consciousness to reveal themselves. It is no longer a matter of merely painting bodies, instead capturing the forces that run through them, to bring to light what is buried and invisible, and to open up the shadows.

Arthur Jafa’s work in the Rotunda, Love is the Message, the Message is Death, transforms the space into a sounding board for the music and social commitment of African American icons such as Martin Luther King Jr., Jimi Hendrix, Barack Obama, and Beyoncé, thus granting them a universal scope. His films, which oscillate between life and death, violence and transcendence, play out as a visual melody inspired by gospel, jazz, and black music. They form a flow of images and sounds that lend their beat to the entire exhibition, in a choreography in which the depicted bodies bear witness to the links between art and life. A rich musical programming in resonance with the exhibition makes ‘Corps et âmes’ a polyphonic event.”

—Emma Lavigne, General Curator, General Director in charge of the Pinault Collection.

Overview of the exhibition

VESTIBULE: Georg Baselitz

“Corps et âmes” begins with work by Georg Baselitz installed in the Vestibule of the Bourse de Commerce. A figure that is innocent from the front and threatening from the back, this cedar wood sculpture coloured with oil paint is a colossal self‑portrait of the artist as a child holding a skull in his hands. Dominating the viewer, the feet solidly anchored to the ground, Meine neue Mütze (My New Cap) (2003) is Baselitz’s first sculptural self‑portrait.

SALON: Gideon Appah / Ana Mendieta

As a prelude to the exhibition, the Salon features a diptych by Ghanaian artist Gideon Appah, The Confidant and The Woman Bathing (2021). Inspired by works by Cézanne, Matisse, and Gauguin, in search of Edenic lands in which the figures of bathers and odalisques curled up in an idyllic landscape evoke a golden age threatened by modernity, Gideon Appah’s work turns perspectives on their head, depicting a world that is both dreamlike and real, and drawing inspiration from the paintings and photographs of post‑independence Ghana. The unreal blue of the bodies evokes a primordial, mythical universe, and the iconography surrounding Ghana’s independence in 1957 and its promise of a rediscovered land enter into resonance with the red blood of Ana Mendieta’s body in Silueta Sangrienta (1975). The body in metamorphosis and as something archaic here aspires to reconnect with foundation myths, to become one with Mother Earth, after the uprooting of the artist’s exile from Cuba to the United States in 1961. The artist’s body melds with the material before reappearing in the form of a silhouette of red lava: an intangible body of which only the radiance of its incandescent aura remains.

THE BODY AS WITNESS

“Inspired by the struggle for consciousness and the resistance struggles of the 1960s tied to the civil rights, feminist, and peace movements, artists use the body as a seismograph and privileged witness to a form of socially committed art that voices the anger of our contemporary world and the ongoing threats to individual integrity. Photography, drawing, sculpture, and painting use the body to testify to their deep otherness and to render visible that which is imperceptible or buried. The works bear traces of the scars of history, taking the pulse and the imprint of individuals who have been invisibilised. They often strip the body bare to reveal more of the soul. They bring out the beauty, humanity, and energy of real and fictional beings who reclaim their rights and their place in history.” Emma Lavigne

GALLERY 4 With: Philip Guston / Duane Hanson

“Marked by the violence and racism of the assassinations of John F. Kennedy and of Martin Luther King, the race riots that erupted from Chicago to Los Angeles to lynchings by the Ku Klux Klan, Philip Guston abandoned the lyricism of abstraction, as he had grown to feel that it was disconnected from the present. He longer felt compelled to paint, instead he wanted to unlearn painting to come as close as possible to the emptiness of reality, or to attempt to depict abjection through the sacrilegious use of the grotesque in cartoon drawings. ‘Paint what disgusts you. … Paint the truth’, the artist has said, groping through both the darkness of the world—like Goya in his black paintings—and pinkish incarnations of the f lesh, for something to emerge, an object or an impression whose organic nature appeals to our humanity. The forms emerge from the limbo of a nocturnal imagination or from the astonishment of embodying, in the solitude of the studio and in the dissonance of the world.

Echoing this deep melancholy, the only escapes that Duane Hanson’s hyperrealist stagings offer us are the ones that the philosopher Emmanuel Lévinas1 calls the ‘face‑to‑face meeting with the other’, in a huis clos in which we become aware of the mortality and vulnerability of the other and of our own responsibility and complicity in their death. His works from the 1960s, such as War (1967) against the Vietnam War, or Riot (1968) bear witness to the race riots and act as political pleas and a call to empathy.

The use of the lifecasting technique inherited from George Segal involves moulding the sculpture directly on living models. This stimulates the emergence of an awareness of the collective body, as the artist often used several models to create an individual sculpture. Here, the confrontation between a black house painter and the self‑portrait as a disillusioned artist testify both to the irreparable separation between these two figures from different worlds and to their proximity, united as they are by the same sense of apparent disenchantment.” Emma Lavigne

GALERIE 7.1 / DOUBLE REVOLUTION STAIRCASE / ENTRANCE OF GALLERY 2 With: Georges Adéagbo / Terry Adkins / Richard Avedon / James Baldwin / Marlene Dumas / Robert Frank / LaToya Ruby Frazier / David Hammons / Anne Imhof / William Kentridge / Sherrie Levine / Kerry James Marshall / Zanele Muholi / Robin Rhode / Auguste Rodin / Lorna Simpson / Kara Walker / Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

The interweaving of texts and photographs between James Baldwin and Richard Avedon, Nothing Personal (1964), also acts as a manifesto that holds up a different mirror to America than the one that diffracts the vain sparkling of a consumer society which struggles to ignore the tarnished mirage of the American Dream. The painful odyssey that the author of Nobody Knows My Name (1961) and The Fire Next Time (1963) composed with his childhood friend Avedon, who turned away from fashion to focus his lens on human rights activists, gives shape to what we don’t want to see: an America of the disenfranchised, of the people left out of its dream.

The legacy of the visual and political struggles of the artists in the Pinault Collection is clear in the works of Kerry James Marshall (Gallery 7.1) and Terry Adkins, caught on the edge of the visible, between appearance and dissipation, as well as in the piece Cloudscape (2004) by Lorna Simpson, whose invisible men and women reveal the major influence of the novel Invisible Man (1952) by Ralph Ellison. For their part, David Hammons’ bodyprints return to the primordial form of the imprint to elicit a sense of belonging to a community, to restore what has been missing to one’s body and soul.

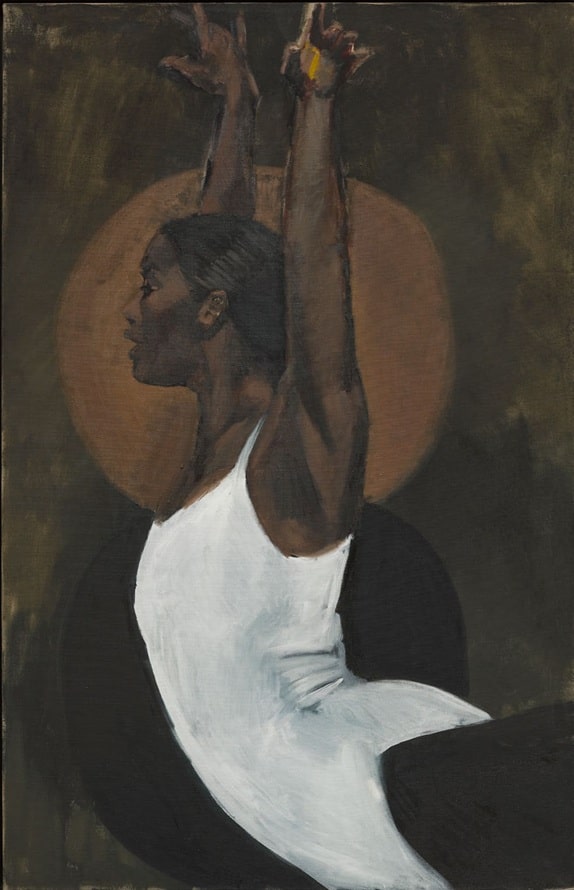

At the same time, the drawings of Kara Walker, William Kentridge (in the double helix stairwell), Robin Rhode (at the entrance to Gallery 2), and Anne Imhof, against the academic tradition of the painted portrait, seize on the fragility of bodies, the lines drawing imperceptible veins on the paper that can be erased, but which take the pulse of these bodies that struggle to exist. It is through her daily practice of drawing that Anne Imhof draws and choreographs her future performance works, in which the flesh of a living body becomes the ultimate visual material through which life manifests itself, as if she were transmitting her own emotions to other bodies. It is reminiscent of the way that Géricault (whom she admires greatly) drew dead bodies in the morgue before giving them a renewed intensity in his large paintings, especially The Raft of the Medusa (1818‑1819). The work of art is no longer a theatrical scene that is removed from reality, instead the very space in which we become aware of art’s ability to make us human in a here and now. In a single gesture, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, a London artist born to Ghanaian parents, hybridises reality and fiction, the history of painting, and the immediacy of the present, all in the flash of the act of painting. Inspired by Manet, Degas, and Goya, she paints powerful portraits of black figures whose clothing and aura provide no indication of their social condition or the era in which they live, thereby imbuing these bodies with a dignity that they had long been refused, as in Light of The Lit Wick (2017), which depicts a majestic, young dancer.

THE BODY EXPOSED

“Inspired by the likes of Edouard Manet’s revolutionary Olympia (1863), which exploded the academic theory of the female nude to create a political manifesto, these artists are liberating the representation of bodies from the shackles of art history. These bodies, in their infinite plasticity, are reified, sexualised, exposed, and exhibited, all the more so when it comes to the bodies of black women who suffer the pain of colonial history. Between the violence of representation, sexism, and the affirmation of a liberated body, the works perform a choreography in which immobility and passivity give way to an activation of rediscovered vital energies. The representation of bodies becomes polyphonic and reveals both the fragility and the pulsating energy of a body retaking possession of its relationship to the other and to the world.” Emma Lavigne

GALLERY 7.2 With: Diane & Allan Arbus / Richard Avedon / Claude Cahun / Marlene Dumas / LaToya Ruby Frazier / Anna Halprin & Seth Hill / Kerry James Marshall / Senga Nengudi / Antonio Oba / Irving Penn / Niki de Saint Phalle

In 1969, American choreographer Anna Halprin refused to stage the violence of the race riots in a performance. In Right On (Ceremony of Us), a workshop that was in part filmed during that same year, she invented a ritual in which black and white bodies that had historically remained separate could come together and dance together for the first time ever. Her humanist thought is reflected throughout the exhibition Corps et âmes.

This gallery features one of Niki de Saint Phalle’s first Nanas, the Nana Noire (1965), inspired by Rosa Parks, emblematic figure of the struggle against racism in the United States. For this artist, the resistance to the subjection of women, the representations of whose forms are excessively fecund and generous, joins the struggle of African Americans who have been victims of racist and sexist violence in American society. A fan of jazz, the artist was also alluding to the singer Billie Holliday, who, like her, was confronted with sexual violence at a very young age. This exhibition of bodies is also manifest in the works of Auguste Rodin (Gallery 7.1) with Iris, Messenger of the Gods (1891), which depicts the Greek goddess headless, without any of her divine attributes. Her naked body with its broadly open legs recalls Gustave Courbet’s The Origin of the World (1866) as she offers herself for everyone to see.

For her painting Candle Burning (2000) Marlene Dumas, who spent a lot of time going to strip clubs, took her inspiration from Polaroids taken of a famous dancer during her contortionist routines performed by candlelight. Marlene Dumas’ relationship to the body is polyphonic and free of all moral notions for being so closely bound up with desire. She questions the hackneyed model of the female nude in art history through painting, the fundamental medium of human contact.

Correspondingly, the self‑portraits of South African photographer Zanele Muholi form part of the militant reappropriation of the representation of bodies and identities. American artist Senga Nengudi, who studied dance for a long time, uses performance to summon the energy of ritual dances from both Africa and Japan. She creates sculptures using pantyhose and performances such as R.S.V.P. (1976‑1978), which consist of choreographed movements through which she studies the extendibility, elasticity, and fragility of the body.

GALLERY 7.3 With: Marlene Dumas / David Hammons / Kudzanai-Violet Hwami / Mira Schor / Wolfgang Tillmans

The exhibition gradually features works that exceed the raw materiality of the body to acquire a phantasmagorical quality, as in Marlene Dumas’ Birth (2018), which reconsiders art history and the figure of Venus by painting the body of a pregnant woman as the goddess of love and fertility. The bodies appropriated by the artist are carnal, liquid, or ghostly, as if they were drowning in the paint’s own fluidity. Her carnal painting touches the soul. The representation of bodies gives way to that of the spirit. Contemporary painting does not hesitate to explore a more symbolic and spiritual dimension, without overlooking political commentary, as in the works of Mira Schor. The multiple, kaleidoscopic images of Kudzanai-Violet Hwami explore the various aspects of identity, as does David Hammons’ Rubber Dread (1989), which lies halfway between a social commentary on physical and social cast‑offs and the ghosts that continue to haunt our society.

THE SOUL WITHIN THE BODY

“At times the works exceed the materiality of the body to take on a phantasmagorical quality in which the body becomes an envelope of flesh and bone, the incarnation of the soul. Such works evoke the primordial archetypes of mythology and ritual. At times they are imbued with the onirism and awareness of the dissipation of the existence of paradises lost in the works of Henri Matisse, Paul Gauguin, and Edvard Munch. Painting takes on a more symbolic and spiritual dimension, without ceding anything to political commentary. Incandescent bodies metamorphose, dance upside down, merge with the earth, and sail towards nothingness. Errant souls perform sacred, ephemeral dances, testifying to the ways in which history uproots and tears things apart. Art is an antidote to the fragility and disappearance of the body.” Emma Lavigne

GALLERY 6 With: Michael Armitage / Miriam Cahn / Peter Doig / Marlene Dumas / Ana Mendieta

Miriam Cahn’s installation RITUALS in Gallery 6 is a meditation on the fragility of our existence and the daily rituals that took place during her father’s final days. The artist replaced the work’s uniqueness with an almost organic rhythm of images that evokes the cycle of Edvard Munch’s Frieze of Life. It is as if Miriam Cahn’s own body had given birth to these works in the act of painting. “An exhibition is a work unto itself, and I see it as a performance”, the artist has explained. The connections she weaves between her works are at times so essential and consubstantial, as they are here, that she invents symbolic spaces, rooms to protect the intimacy that connects them and which form a small theatre. “I’m interested in the interactions between the image and the viewer,” Miriam Cahn explains. She has often said that often, as a young artist, she wanted to translate into her work “that burst of enthusiasm that I used to feel when I used to go to the theatre”.1

These ritualised scenes continue in the dialogue between the works of Peter Doig and Michael Armitage. Music becomes both an earthly and a dreamlike presence, a balm for the soul, whether it’s the boat called the House of Music (2023) sailing towards nothingness to meet the very real musicians in the painting Dandora (Xala, Musicians) (2022), in which a group of men play the Xala in an open‑air dump in the heart of Nairobi. The piece by Marlene Dumas, Einder (Horizon) (2007‑2008), with its fresh flowers painted on her mother’s tomb, is “portrait of her without painting her. I tried to paint something endless”, the artist has said. The work’s title suggests a sense of the finite, an unattainable horizon, a journey towards a landscape of the beyond, which is extended in Ana Mendieta’s video Flower Person, Flower Body (1975), in which flowers float and scatter amidst the waves, dispersing like a libation.

GALLERY 5 With: Georg Baselitz / Ana Mendieta

At the end of the exhibition, Georg Baselitz’s monumental masterpiece Avignon (2014) completes this dance of bodies. In the darkness, the eight dramatic and spectacular paintings hung in this space form a huis clos, a theatre in which the artist’s aging body is the sole actor. They were first exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 2015, curated by Okwui Enwezor. Inspired by Pablo Picasso’s last paintings as well as works by Lucas Cranach, Egon Schiele, and Edvard Munch, these bodies seem to “dance upside down”, in the poet Antonin Artaud’s words.

Like the promise of a rebirth, a continuity of life after death, Ana Mendieta’s chrysalis‑body becomes a butterfly, appearing as a light in the darkness.

GALLERY 3 Deana Lawson Curated by Matthieu Humery, Photography Advisor, Pinault Collection

On the first floor, the Bourse de Commerce hosts the first solo exhibition in France by Deana Lawson. The photographer’s work closely examines the human experience, intertwining personal, collective, and imagined histories to create a distinct form of storytelling. While Deana Lawson utilizes aspects of documentary tradition, her practice transcends observational photography, transforming it into a medium of powerful expression and critique. Her portraits create a narrative that bridges the artist’s own biography, symbolism, and cultural observation, offering a profound exploration of contemporary identity.

PASSAGE / THE ENGINE ROOM Ali Cherri Curated by Jean‑ Marie Gallais, Curator, Pinault Collection

“The Passage of the Bourse de Commerce is hosting the works of Ali Cherri, artist living in France. His youth was marked by the civil war in Lebanon, especially by the plundering, theft, and trafficking of artworks that such belligerence provokes. In taking over the twenty-four display cases, the consummate museum device for exhibiting objects, his work is also inspired by film and its twenty-four images per second. His sculptures have been conceived as ghostly flashes occupying a liminal space between life and death and between past and present, and which ask us to reflect on the age-old manipulations of cultural artifacts.” Emma Lavigne

“Cherri wrote, ‘And then came cinema to resuscitate the body. The history of cinema is a history of dead people who survive in images. Cinema has always been a question of ghosts, be this for technical reasons (light projection, cross‑fades), genealogical reasons (influences from phantasmagoria and magic lanterns), and especially for poetic reasons (the characters dying on screen and coming back to life with each screening). By recording and preserving traces of bodies, cinema becomes a way to bring the dead back to life on screen and to reawaken the souls of inert bodies’.3 In his film Somniculus (2017), which was shot in Paris, Ali Cherri used this ghostly aspect of film by replacing the bodies of the actors with artworks and objects filmed in empty museums. By reversing the recurrent analogy between museums and cemeteries, especially in a postcolonial setting (Statues Also Die by Alain Resnais, Chris Marker, and Ghislain Cloquet, 1953), Ali Cherri prefers to see these objects as temporarily asleep—in Latin, somniculus means light sleep—and the museum as a dormitory.

In continuing this project, sculptures and artifacts arranged as miniature tableau vivants sleep and awaken in each of the display cases at the Bourse de Commerce. With a sculptor’s gestures, Ali Cherri has allowed these artifacts to hybridise, to be translated from one material to another, the fragments reconstituting a new whole. He creates chimeras by combining archaeological finds with his own creations. ‘The grafts I make in my series of sculptures constitute a form of solidarity between bodies that have been shattered, fragmented, and violated, and which create a community by becoming fused together’, he explains. These objects that have been resuscitated or that have survived tumultuous pasts, cast‑offs that were deemed unworthy of preservation but which have borne witness to countless exchanges and peregrinations: eyes torn out of Egyptian sarcophagi and counterfeited when they became fashionable in European collections, fake curios, and copies of ancient pieces are fused like distant civilisations that cohabit and take root in each other.” Jean‑Marie Gallais

WHEN?

Wednesday, March 5 to Monday, August 25, 2025

Opening hours:

Mon – Sun: 11 am – 7 pm

Friday: 11 am – 9 pm

Closed on Tuesdays

WHERE?

Bourse de Commerce

2 rue de Viarmes

75001 Paris

COST?

Regular: 15 EUR

Reduced: 10 EUR